Taub, G. E., & McGrew, K. S. (2014). The Woodcock–Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities III’s Cognitive Performance Model Empirical Support for Intermediate Factors Within CHC Theory. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 32(3), 187-201. http://www.iapsych.com/articles/taub2013.pdf

CPM – cognitive

performance model was developed by Richard

Woodcock, one of the developers of the Woodcock Johnson test in 1997. This cognitive model assumes that

intelligence is composed of three systems:

The thinking system (or thinking

ability), which accounts for performance in tasks that require problem solving,

thinking and complex executive functions.

The quality of a person's learning depends on

his thinking ability. The thinking ability

includes the ability to abstract ideas, to conceptualize and to solve new

problems, to process visual and auditory stimuli and to learn and to retrieve

information from long term memory (in CHC terms, fluid ability, visual

processing, auditory processing and long term storage and retrieval). Limitations in one of these components affect

the whole system, limit new learning and may require a change in instructions.

The cognitive efficiency system, which allows

for optimal use of the mental resources.

This is the ability to perform a task quickly and with attentional

focus, and the ability to reach automatic performance. This system reflects the relation between

quality of performance and effort. The

cognitive efficiency system includes the ability to hold a few pieces of

information in awareness and to perform manipulations on them and the ability

to process information quickly (in CHC terms, short term memory and

visuospatial ability). Limitations in one

of the component of the cognitive efficiency system affect the whole system and

require adaptations in instruction methods and in testing.

Funds of acquired

knowledge,

which include a person's crystallized

knowledge, oral language, math skills,

reading and writing skills. The quality

of learning and performance are dependent on the relevant knowledge a person

has. Once a piece of information is

learned, it can become a basis for new learning. If a piece of information was not learned, it

can become an impede future learning.

The funds of acquired knowledge are mutable: instruction strategies and opportunities for

enrichment can affect a person's level of performance in this system.

A child's functioning in every task is a

result of the combined action of the three systems and facilitating/inhibiting

factors:

Facilitators/inhibitors affect performance for better or for

worse. Sometimes they are internal

(health, emotional state, motivation), sometimes they are external (the

presence of visual or auditory distractions, instruction method, the features

of a specific tests the child takes).

Significant health issues that may interfere with school attendance may

cause loss of learning opportunities.

Low motivation for learning or low interest in the contents learned may

affect the extent of effort a person makes.

Cognitive styles or temperament, like impulsivity, may negatively affect

the quality of a person's work. Other

factors, like emotional stability, organizing ability and concentration

ability, may affect learning for better or for worse.

The CPM model was developed theoretically,

not on the basis of empirical findings.

Despite the potential of this model, there is still little empirical

research testing it. One of the ways to

conceptualize the model is through considering the CPM systems as intermediate

abilities between g and the broad CHC abilities. Keith (2005) tested this

using 22 tests from the Woodcock–Johnson test battery (WJ III). He included

Cognitive Efficiency and Thinking Ability as intermediate factors within the

CHC model. The Verbal Ability factor was not included in this model because the

CPM’s Verbal Ability factor and the second-order broad CHC factor, Crystallized

Intelligence, are indistinguishable. Keith found the categorization of Cognitive

Efficiency and Thinking Ability as intermediate factors within the CHC

theoretical model resulted in an improvement in the model’s fit, when compared

with the CHC model without intermediate CPM factors. Keith further noted that within this model,

the Thinking Ability factor and g were indistinguishable, so he removed

the Thinking Ability factor. In his simpler model, processing speed and

short-term memory loaded on the intermediate Cognitive Efficiency factor (both

the Verbal Ability and Thinking Ability factors were excluded from the

analysis). Keith found that this parsimonious one-factor CPM model provided the

best fit to the data.

Taub and McGrew (details and link above)

also tested the CPM model using the WJ3COG standardization sample in the age

range of 9-19. Like Keith, they measured

every broad CHC ability with three tests.

Thus they included the oral language test from the WJ3ACH as a measure

of comprehension knowledge. Taub and

McGrew tested six versions of the CPM (and of the structure of intelligence):

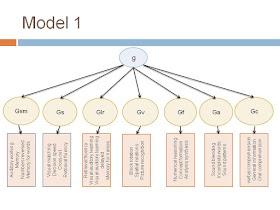

Model 1: the traditional

CHC-based measurement model:

click on image to enlarge

Model 2 (pictured below) is the traditional CPM model, which

includes two Cognitive Performance factors as intermediate factors lying

between the second- and third-order factors within the traditional CHC-based

measurement model. The Verbal Ability factor

was eliminated from Figure 2 because it is an intermediate latent variable with

only one indicator, Crystallized Intelligence (Gc). Thus, the variance

accounted for by Verbal Ability in Model 2 is isomorphic with second-order

broad CHC factor, Gc.

Model 3 (pictured below). This

model is a replication of Keith’s one-factor CPM wherein the Thinking Ability

and Verbal Ability factors are subsumed by the third-order general ability

factor.

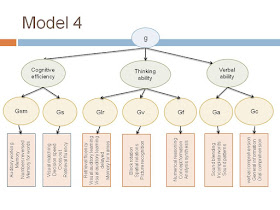

Model 4 ( pictured below) is similar to Model 2 with two

differences. First, Model 4 includes the CPM factor, Verbal Ability. To provide

adequate construct representation of Verbal Ability in Model 4, a second

indicator was added, Auditory Processing (Ga). In this model, the variance

accounted for by the broad CHC factor Ga was moved from the CPM Thinking

Ability factor to the CPM Verbal Ability factor. An

inspection of the correlations between the WJ III tests measuring Ga abilities

with Verbal and Thinking abilities revealed stronger relations with the former.

Model 5 (not pictured) is a hybrid model. In this model, Ga shares

variance with Thinking and Verbal ability. Thus, Model 5 incorporates the

traditional placement of Ga as a component of Thinking Ability (Figure 2) and a

component of Verbal ability as presented in Figure 4.

Model 6 (pictured below) is similar to Model 4; however, in

Model 6 the intermediate CPM factor Thinking Ability is considered isomorphic

with the third-order g factor.

The model that provided the best fit to the data was

model 6.

The replication and finding of empirical support

for the existence of intermediate factors within the CHC model suggests that

researchers may need to account for the existence of intermediate factors

within the CHC framework. It is worth

noting, that all models provided an improved fit over Model 1, the traditional

CHC based theoretical measurement model. This indicates that the inclusion of

intermediate factors within a traditional CHC theoretical model provides an

improvement in overall model fit.

Does

it mean that the CHC model should be changed?

We must remember that these are two studies done on a single

intelligence test battery. More evidence

is needed from other test batteries.

אז מדוע בגרסה הישראלית משתמשים במדול של CPM?

ReplyDeleteתודה מייקל על התגובה. הגירסה הישראלית תואמת למבחן האמריקני בשני המודלים - CHC ו - CPM. זאת בהתאם לחוזה עם מחברי המבחן האמריקנים. סמדר

Deleteאיך שאני מבין, יש בעיה עם מודל הCPM ברמה הקונצפטואלית, לכן אי אפשר להמשיך לבדוק את היכולת כי הגדרת היכולת שלעצמה בעיתית

ReplyDeleteעל כל מודל יש ביקורת.

ReplyDeleteגם מודל CHC עוד יתפתח וישתנה.

לגבי CPM, כשמשתמשים ביכולת ידע נרכש, צריך לזכור לכלול בו גם קריאה, כתיבה, חשבון ולא רק את הידע המגובש.

צריך לזכור שהוודקוק הישראלי מודד רק חלק מהיכולת ידע נרכש.

הוודקוק בגירסה האמריקנית מכיל את כל מרכיבי היכולת הזו.