Comprehension

knowledge is the breadth and

depth of skills and knowledge that are valued by one's culture. Comprehension knowledge includes the ability

to understand spoken language, the breadth of a person's lexicon and general knowledge,

and a person's awareness of grammatical aspects of language.

Is comprehension knowledge an independent

ability or a product of the application of other cognitive abilities? In other words, is it a cognitive ability,

like fluid ability, short term memory and long term storage and retrieval or is

it an area of achievement like reading, writing and math?

As will be discussed below, it's possible

to conceptualize comprehension knowledge both as an ability and as an

achievement.

Language

impairment (LI) is an impairment

in expressive and/or receptive language development in the context of otherwise normal development

(i.e., nonverbal IQ and self-help skills).

Language impairment interferes

with activities of daily living and/or academic achievement. LI

children usually have poor comprehension knowledge, although LI will not always

manifest in poor scores on intelligence subtest scores measuring comprehension

knowledge. The reason for that is that

these tests do not assess all aspects of comprehension knowledge and especially

not the child's command of grammar and syntax.

A broad distinction can be drawn between

two classes of LI model: those that regard the language difficulties as

secondary to more general nonlinguistic deficits, and those that postulate a

specifically linguistic deficit.

The best known example of the first type of

model is the rapid temporal

processing (RTP) theory of Tallal and colleagues, which maintains that

language learning is handicapped because of poor temporal resolution of

perceptual systems. The first

evidence for the RTP theory came from a study where children were required to

match the order of two tones. When tones

were rapid or brief, children with LI had problems in correctly identifying

them, even though they were readily discriminable at slow presentation rates. Children who have poor temporal resolution

will chunk incoming speech in blocks of hundreds of milliseconds rather than

tens of milliseconds, and this will affect speech perception and hence on

aspects of language learning.

In CHC terms Tallal's theory can be conceptualized

as poor auditory processing

and maybe also poor processing speed that

underlie LI.

Another theoretical account that stresses

nonlinguistic temporal processing has been proposed by Miller, who showed that

children with LI had slower

reaction times than

did control children matched on nonverbal IQ on a range of cognitive tasks,

including some, such as mental rotation, that involved no language. Unlike the

RTP theory, this account focuses on slowing of cognition rather than

perception.

A

more specialized theory is the phonological

short-term memory deficit account of LI by Gathercole & Baddeley. These authors noted

that many children with LI are poor at repeating polysyllabic nonwords, a

deficit that has been confirmed in many subsequent studies. This deficit has

been interpreted as indicating a limitation in a phonological short-term memory

system that is important for learning new vocabulary and syntax.

Ullman argues that our use of

language depends upon two capacities: a mental lexicon of memorized words and a

mental grammar of rules that underlie the composition of lexical forms into

predictably structured larger words, phrases, and sentences. On this

view, the memorization and use of at least simple words depends upon an associative

memory (the ability to learn links between pairs

of stimuli, for example between the sequence of phonemes forming a word and its

meaning. Associative memory is a narrow

ability within long term

storage and retrieval). The acquisition and use of grammatical rules depends upon procedural learning and memory (for instance, learning the rule/procedure of past tense

as the addition of "ed" (walk – walked)). Procedural memory enables us to learn many

motor and cognitive "skills" and "habits" (e.g., from

simple motor acts to skilled game playing). LI,

argues Ullman, is caused by poor associative and/or procedural memory. LI is not a specifically linguistic disorder

but is rather the consequence of an impaired system that will also affect

learning of other procedural operations, such as motor skills.

To all

this we can add Cattell's investment theory.

Cattell argued that crystallized knowledge develops through

the investment of fluid

ability. Babies are born with

fluid ability only, which they use in their first encounters and experiences

with the world. Explicit and implicit memories formed in the baby's mind

by these encounters and experiences gradually form his reservoir of

crystallized knowledge. From now on, the baby tackles new experiences

equipped with both fluid ability and crystallized knowledge that he already

acquired. The more knowledge he acquires, the better is his ability to

cope with situations he encounters, and the less fluid these situations become.

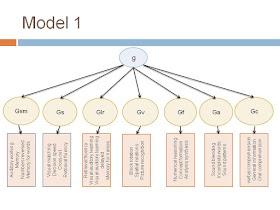

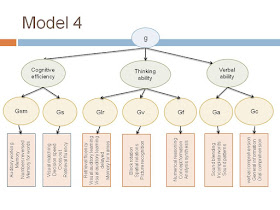

The theories presented above enable us to

consider comprehension knowledge as an area of achievement. When a child performs poorly in an area of

achievement (reading decoding, reading comprehension, writing and spelling,

math computations or math reasoning) we look for the cause of his poor

performance among the cognitive abilities (fluid ability, short term memory,

long term storage and retrieval, processing speed, visual processing, auditory

processing, comprehension knowledge). If

comprehension knowledge is also an achievement area, when a child has poor

comprehension knowledge, we should look for the reason for that in one of these

cognitive abilities: fluid ability,

short term memory, long term storage and retrieval, processing speed, auditory

processing and perhaps also visual processing (I don't know a theory linking LI

to poor visual processing).

But comprehension knowledge is different

than other achievement areas. Reading,

writing and math are acquired mostly through formal instruction (there are

aspects of arithmetic that are acquired naturally without instruction – like counting

procedures). Native language is acquired

mostly informally – mostly spontaneously/implicitly. Formal instruction enriches and develops native

language.

The authors above argued that

domain-general deficits in cognitive and perceptual systems are sufficient to

account for LI. This position differs radically from linguistic accounts of LI,

which maintain that humans have evolved specialized language learning

mechanisms and that LI results when these fail to develop on the normal

schedule . A range of theories of this

type for LI focus on the syntactic difficulties that are a core feature of many

children with LI. Children with LI tend to have problems in using verb

inflections that mark tense, so they might say “yesterday I walk to school”

rather than “yesterday I walked to school.” Different linguistic accounts of

the specific nature of such problems all maintain that the deficit is located

in a domain-specific system that handles syntactic operations and is not a

secondary consequence of a more general cognitive processing deficit.

Pennington,

B. F., & Bishop, D. V. (2009). Relations

Among Speech, Language, and Reading Disorders. Annu. Rev.

Psychol, 60,

283-306. http://www.du.edu/psychology/dnrl/Relationsamongspeechlanguageandreadingdisorders.pdf

Schneider,

W. J., & McGrew, K. S. (2012). The Cattell-Horn-Carroll model of

intelligence. Contemporary

intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and, (3rd), 99-144.